Wine Writing In Extremis

posted 6th October 2024

As I write this, I have just finished a week's work as speaker on a Noble Caledonia 'wine' cruise in Bordeaux. There were a hundred and twenty-four participants, mostly mature people, with varying levels of wine knowledge from very basic to connoisseur. Every morning I gave a talk for an hour, as the ship made its way along the rivers or Gironde estuary. Almost all the guests attended each and every talk, thirsty for insight into Bordeaux, its wines and the wine world generally. Now, with apologies to Neil Oliver, here's the thing: when I asked who bought any wine magazines, the answer was nobody. Who read newspaper wine columns? - nobody. Who paid to subscribe to websites or blogs, e.g. www.jancisrobinson.com? - nobody. A few of the guests did say that they read this (free) blog, and three people said they owned a wine book or two. But to put it bluntly, of over a hundred people who said they drank wine on an almost daily basis, almost nobody wanted to read what today's cohort of wine writers had to say. Yet they wanted to hear me speak, everyday. I am not for one moment suggesting that I am a better writer, or speaker, than many of my colleagues, but surely one of the key reasons to do this job is to inspire?

Until a few years ago I lived, when in UK, in a popular Cotswold village. The local newsagent stocked a sizeable array of magazines. Not a wine magazine, not even Decanter, the onetime self-styled 'world's best wine magazine'. There were, however, 13 railway mags. Enough to make you turn to drink. Several of my colleagues have cancelled their subscriptions to Decanter, and I cancelled mine when I found that I had three recent, unopened, issues. I had not been inspired. When I showed some of the magazines to Loire Valley winemakers at a recent event, the shaking of heads almost created a whirlwind. 'This is the end', was one comment, 'it is nothing more than a shopping list'.

Of course, today there are many other methods of wine communication other than 'traditional' writing, including the work of the so-called influencers. But why are today's wine writers failing to attract wine loving readers? And it is of great concern to wine producers that Millennials and Gen. Z are not turning on to wine as preceding generations did. The 2023 State of the Wine Industry Report shows that the largest drop in consumption share was with young wine drinkers - millennials and Gen Z. The largest increase in consumption was with people over 60, the Baby Boomers. There are many millennial wine writers, trying to have a positive impact, but they struggle to make a living in a world where fees for wine articles are on the floor. Some write 'sponsored' articles, to make ends meet, although perhaps the dark side of sponsorship manifests itself with the influencers. For the avoidance of doubt, let me declare here that I do accept expenses paid visits to wine regions, and hospitality hosted at wineries. I do not accept any payment should a write about the region or wineries in question.

Well, we can place the blame at the doorsteps of:

the writers,

editors,

publishers,

cancel culture and woke.

But let us go back 190 years to perhaps the birth of modern wine writing. In 1833, The History and Description of Modern Wines by Cyrus Redding was published. Much of Redding’s tome of over 400 pages will strike a chord with the knowledgeable wine connoisseur of today. He details the vineyard land planted, the vines, production methods, and styles and qualities of wines produced throughout Europe, South Africa and the Americas. Writing of Château Haut Brion, he notes that: ‘The flavour resembles burning sealing wax; the bouquet savours of the violet and raspberry.’ In an appendix, Redding lists ‘WINES OF THE FIRST CLASS’. The list begins with Burgundy, commencing with Romanée Conti, Chambertin and Richebourg, which are described as ‘the first and most delicate red wines in the world, full of rich perfume, of exquisite bouquet …’. Next comes Gironde (Bordeaux), beginning with Lafitte [sic], Latour, Château Margaux and Haut Brion. Of Redding’s other first‐class wines, perhaps the inclusion of Lacryma Christi is the only one that would raise eyebrows today.

When, in 1920, Professor George Saintsbury’s Notes on a Cellar Book was first published, the 75‐year‐old author could have had no idea that sharing his opinions of wines he had drunk over more than half a century would have such an impact upon wine lovers. Redding detailed vinous facts (as then perceived), and basic tastes and perceptions. Notes on a Cellar Book was perhaps the beginning of a new school of art, and the precursor of a new science, of the assessment of the tastes and quality of wines, at times looking beyond simplistic descriptors. Saintsbury was to become an icon to the oenophile, having both a prestigious wine and dining club and a flagship Californian winery named in his honour. The clarets of 1888 and 1889 were, to Saintsbury, reminiscent of Browning’s A Pretty Woman and the red wines of the south of France ‘Hugonic in character’.

Today’, most writers would not dream of using such analogies, and if they did, the copy is unlikely to pass the publisher's editorial gaze. Today's wine writer/critic is, rightly or wrongly, usually more concerned with the awarding of points than allusions to Browning or Hugo. Today, the professional writer also strives to be objective in the assessments made, something that Saintsbury would never claim to be.

Two year's ago a writer colleague penned an article defending the use of terms such as 'feminine' to describe a wine. Such was the publisher's angst that the article was put before the management committee, who pulled the piece on the grounds that it was sexist. A year earlier the world of a well-know whisky writer, Jim Murray, fell apart when he was cancelled following an Instagram post by rival writer Beck Paskin. To quote from the Daily Mail 'Her allegation was that because 34 of Jim's 4,300-plus tasting notes in the 2021 edition of his Whisky Bible referred to whisky being 'sexy' and that also, in a few more, he 'objectifies women', by comparing drinking whisky to having sex, both he and his bible were sexist and a disgrace to the industry. s published an article: Sexism In Whisky: Why You Shouldn’t Read The Whisky Bible. The conglomerates owning numerous distilleries quickly cancelled Mr Murray. He soldiers on, still self-publishing the book every year. For reviews, and observations on his cancellation see: Jim Murray

Edmund Penning-Rowsell, wrote about wine for over 40 years. He had lengthy tenures as the correspondent for County Life and Financial Times. His seminal work The Wine of Bordeaux, first published in 1969, went into six editions. Edmund, painted a picture and was unafraid to expound his scholarly knowledge, giving the reader a deep understanding.

Other passionate and writers of the era included André Simon and Cyril Ray. Both Penning-Rowsell and Ray were socialists, and it is interesting to note that their political opinions never tarnished their works, unlike many of todays writers (perhaps including yours truly).

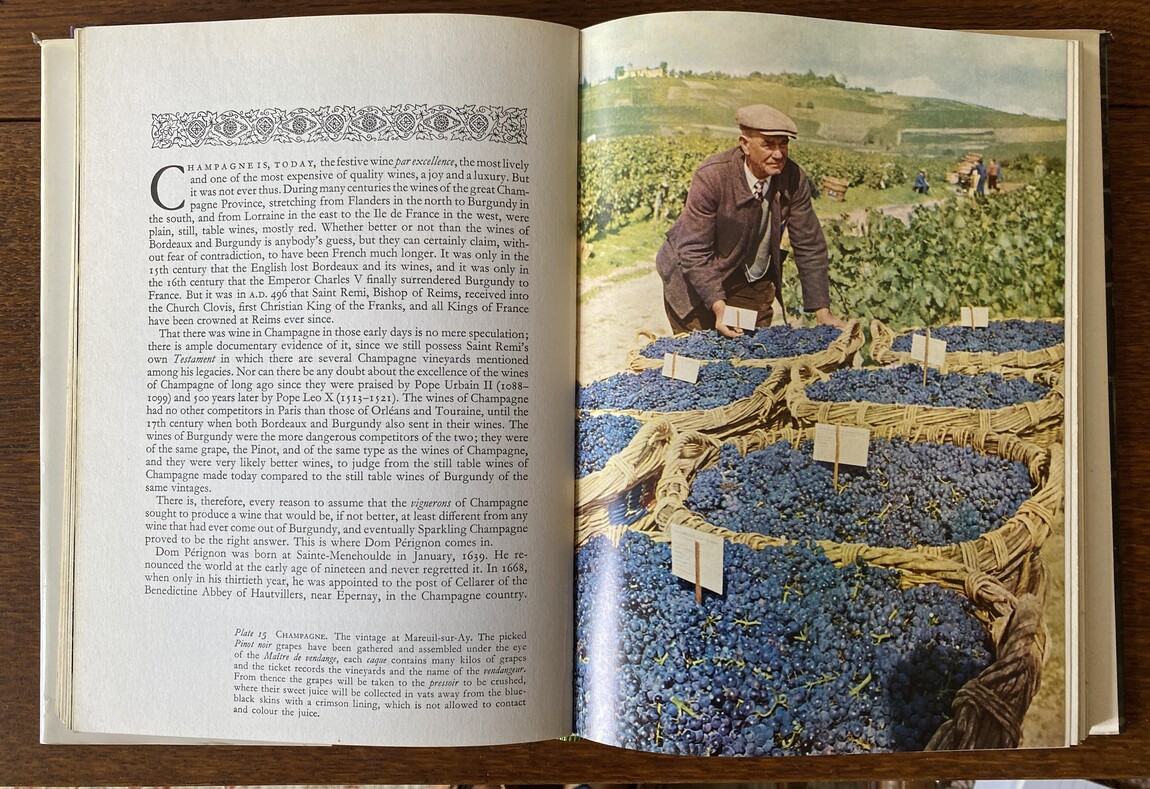

In 1971 the first edition of Hugh Johnson's World Atlas of Wine was published. His excellent first book Wine had been issued in 1966, but the impact of The World Atlas cannot be overstated, and without doubt it was the book that led a new generation to become wine lovers. I was one of these. A visit to the wine merchant was like a tour of Europe, with just a glimpse of the New World, that was yet to make major inroads into the UK market. I wanted to touch those bottles with all the distinctive shapes that one could find at the time. I wanted to smell the wines, to taste them. The Atlas was full of facts, figures and, of course, maps. Hugh was never afraid to state opinions, but made few judgments. The work is now in its 8th Edition, co-authored by Jancis Robinson.

So I look back to try and discover what the works of these writers and authors had that is lacking today. I realise it is perhaps what they didn't have that is key to their greatness. The didn't judge wines quantitively by scoring points, although observations and qualitative opinions were always present. They were never afraid to speak their mind. They didn't fear subjectivity, and they were never hostage to their editors, or their readers. Other than for legal reasons there was no "you can't say that." They recognised that the appreciation of fine wine is culture, and is enhanced by the taster being informed and given the tools to make their own judgments. And their writings are as alive today as they ever were.